International

THE FORGOTTEN VICTIMS OF THE INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL COURT

by Ariane Puccini with Camille Jourdan

12min

It wasn’t until 2016 that the International Criminal Court — which has the jurisdiction to prosecute high-profile war criminals — handed down its first conviction for sexual violence. Within the court, a toxic mix of internal dysfunction, lack of funds and investigations carried out in undue haste combine with political maneuvering to compromise the ICC’s mission of halting impunity. Zero Impunity investigates what is going on behind the scenes in this judicial failure.

«The anonymous, blurry silhouette of “Madame Witness” appears on the flat screen in the courtroom. In a computerized voice, she speaks a few words in Sango, the primary language of the Central African Republic.

Madame Witness isn’t sitting in the courtroom of the International Criminal Court (the ICC) in The Hague, in the Netherlands. She is more than 5,000 kilometers away in Bangui, the capital of the Central African Republic.

“Madame Witness, you are present today thanks to video technology, to speak to us about what you saw as well as your concerns,” says Sylvia Steiner, the Brazilian judge who is presiding over this trial.

Long seconds of silence elapse after each sentence spoken by the witness as her words are translated into French and English, the two working languages of the magistrates, lawyers and bailiffs from five different continents who make up the ICC. Today—May 16, 2016—is a historic day. After 330 days of hearings, a military chief has been convicted of rape as a war crime and a crime against humanity– for the first time in the history of the court.

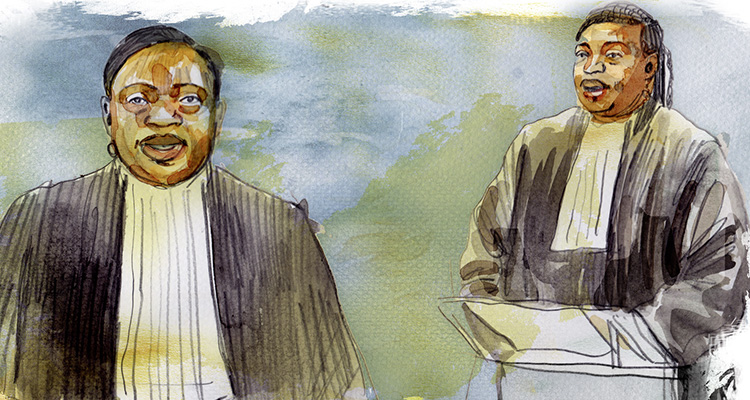

- Brazilian judge Silvia Steiner (right) chaired the trial of Jean-Pierre Bemba (left). (© Damien Roudeau – 2017)

In this sterilized room, the former Congolese statesman Jean-Pierre Bemba, who stuffed into a dark suit and supervised by two police officers, has lost his splendor.

With a bleak expression, he stares at the screen as the witness testifies—his head sunken into his imposing shoulders. Sometimes, his eyes lift to the sparsely populated rows where a handful of people observe the trial. Mute, he has the resigned expression of someone has already accepted his fate.

Indeed, several months before– on March 21, 2016– Bemba had already been found guilty of two counts of crimes against humanity (murder and rape) and three counts of war crimes (murder, rape, and pillaging) for the crimes committed by the soldiers under his effective authority. The trial today will determine how many years he will be imprisoned for the acts of violence committed by his troops.

Madame Witness is one of 5,229 female victims of violence perpetrated between October 26, 2002 and March 15, 2003 in the Central African Republic by the 1,500 men of the Movement for the Liberation of Congo (MLC), the militia founded by Bemba. A frightening majority of these victims were raped. Today, the judges will hear testimonies from two of these victims, Flavie* and Mélanie*. Both of these women’s lives were deeply, irreparably scarred by the abuse that they endured at the hand’s of Bemba’s men.

- Jean-Pierre Bemba during his trial. (© Damien Roudeau – 2017)

These women’s ordeal began when Bemba’s troops came to the aid of Ange-Felix Patassé, the then-president of the Central African Republic (CAR), who was threatened by a coup d’état led by his political rival François Bozizé and his rebels.

Convinced that a majority of Central African civilians had supported Bozizé’s men in their attempt to overthrow Patassé, Bemba and his fellow MLC chiefs instructed their troops to launch a vast punitive operation. At the time, Flavie says she was 15 or 16 years old. The teenager was kidnapped by Bemba’s men, along with her aunt. The two women were taken to a MLC camp.

“When I arrived at their base, one of their chiefs dragged me into an abandoned home […] and raped me,” Flavie recalls.

After that, Flavie was imprisoned with other women, some of whom were as young as 13, and forced to move along with the troops. She was raped every day. Eventually, Bemba’s men retreated back to the DRC, bringing Flavie with them. There, she found out she was pregnant and was forced to live with one of her rapists. Her first child died early, but Flavie soon gave birth to a second.

After four years, Flavie and her daughter managed to flee the DRC. They made their way back to the CAR to reunite with Flavie’s family, who had given their daughter up for dead. Flavie’s aunt—who had also been kidnapped and raped by Bemba’s men—had also made it back alive. However, return to normal life was impossible for these women.

Flavie’s aunt, who had contracted HIV, was unable to access treatment and soon died. Bemba’s men had taken everything from Flavie’s family and they were now living in extreme poverty. Flavie couldn’t return to school. Stigmatized by her neighbors, Flavie decided to leave her hometown and move to Bangui, the capital.

Flavie did eventually get married. However, today, she is a widow, left alone to support her four children as her in-laws rejected her when they found out about her rape. Flavie has no income and is suicidal. She and her children now live with an aunt. Flavie’s oldest daughter doesn’t know she was born of rape.

“The ICC’s ruling won’t change my living situation,” she says. “But someone must pay for the violence that was perpetrated.”

Justice was served for Flavie, Mélanie and the other victims of the brutal campaign led by Bemba’s men in the Central African Republic. However, they are the only ones to achieve this minor success. All of the other victims of sexual violence who have sought justice through the ICC haven’t had that chance.

It took 14 years for the court to sentence a high-ranking official for sexual violence, even though sexual violence is considered a crime under the Statute of Rome, the founding text of the ICC.

However, since the ICC was created in 2002, the court has only accepted to examine about a third of cases involving sexual violence. Moreover, out of the only three cases including charges of sexual violence tried by the court, two ended with acquittals—a surprising record considering that all of the situations subject to ICC investigations have been the site of mass sexual violence. Even in the DRC– a country that is notorious for widespread instances of rape–the court has not achieved even a single conviction. This failure results from a combination of lack of funds and the misguided methods of the ICC.

Investigations: undue haste

and frequent setbacks

The ICC Prosecutor is at the very heart of the system that launches investigations, determines investigation strategies and identifies suspects. When Luis Moreno-Ocampo became the very first person nominated to this post in 2003—shortly after the creation of the court– he was tasked with identifying goals for his team.

However, when he took office in 2004, the ICC was still taking shape. Just about everything still needed to be done, including recruitment of personnel, organization and the creation of different services. This made for laborious beginnings for the Office of the Prosecutor.

Investigators had to start at zero. In the first few months, there were only two investigators covering the entire Democratic Republic of Congo. Working conditions were difficult—they didn’t have an office or a car and they weren’t provided with housing. Security in the country remained uncertain. However, after the first wave of recruitments, the ICC investigators working on the DRC increased: by 2005, there were 12 of them. However, amongst their number, there were few police officers.

- Argentinean magistrate Luis Moreno-Ocampo was the first ICC prosecutor from 2003 to 2012. (© Damien Roudeau – 2017)

That was how Moreno-Ocampo wanted it. The exuberant Argentinian prosecutor saw himself as the herald of a new age of international criminal justice.

“Think out of the box!” he would exclaim to his skeptical team.

“This kind of declaration drove many of the legal experts crazy!” recounted Sacha*, another employee of the court.

Moreno-Ocampo was against the idea of recruiting police officers in his teams and preferred former NGO employees, who he thought to be more familiar with the geopolitical context of the countries that they would be working on.

“We have experienced that in many cases the national police investigators in countries had developed contacts and obtained sources within the militias under investigation,” Moreno-Ocampo stated in an email exchange with Zero Impunity. “Investigators with a different [non-police] background developed sources within the victims’ communities. We just used different approaches.”

For some people who worked within the Office of the Prosecutor, Moreno-Ocampo’s reluctance to employ police officers as investigators was linked to his own personal story and that of his country.

Moreno-Ocampo participated in the trial of the former military junta in his native Argentina in the 1980s. That investigation taught Moreno-Ocampo to work with NGOs instead of the police, many of whom had closely collaborated with the former regime.

While “brilliant,” the young ICC recruits who had formerly worked with NGOs “didn’t know how to collect proof, carry out rigorous interrogations or manage sources,” said Denis*, an ICC employee who knew the prosecutor and who agreed to speak with Zero Impunity. This lack of experience was enough to slow down investigations that were already progressing with great difficulty.

However, the impulsive Argentinian was determined to prove to the world that the court had power and drive. No matter the lack of funds, it was important to rapidly bring cases in front of the judges, who were becoming impatient.

The prosecutor decided to focus his team’s efforts on isolated massacres and targeted incidents. It was a method that, for some, was much too narrow.

“The likelihood of stumbling upon an incident that we could trace back to a high official were slim,” Denis said.

The prosecutor made “abrupt changes” to the focuses of the investigations that were being led by his teams, according to Camille*, a former court employee. Investigators were exploring leads on several massacres where rapes were committed—which could have been traced back to the orders of high-ranking officials– but were forced to suddenly abandoned their research because of time pressures.

Moreno-Ocampo wanted to strike quickly and powerfully, especially when, in 2006, the court caught its first big fish, Thomas Lubanga Dyilo, a Congolese war chief, who was handed over to the ICC by authorities in Kinshasa. Moreno-Ocampo made a strategic choice to focus on what happened to child soldiers conscripted in Lubanga’s militia. Because of this narrow focus on child soldiers, all of the sexual violence committed by the militia would be set aside.

According to former ICC employee Camille, certain NGOs that had an “in” at the ICC had suggested the theme of this investigation. The West was rightly horrified by the conscription of child soldiers. However, for the Congolese, “the infractions that caused the most suffering for the population were the raping and pillaging,” Camille said.

Perhaps the prosecutor thought he had stumbled on a case that would be easy to carry out, as well as being symbolic. However, the teams working for the Office of the Prosecutor started asking an important question: “How do you prove the age of children in a country where birth records aren’t reliable?” asked Camille.

These were questions that Moreno-Ocampo disregarded when he threw himself into this crusade. He said criticisms and differences of opinion were to be expected.

“We were a global start up working for a global audience with different opinions,” Moreno-Ocampo said in an email to Zero Impunity. “At the beginning, it was very difficult to harmonize the practices, creating disagreements.”

However, tensions continued to grow within the Office of the Prosecutor and Moreno-Ocampo’s heavy-handedness didn’t help matters.

Between 2005 and 2007, frustration, inability to understand the strategies used in investigations and erratic changes to objectives pushed a part of the Office’s workforce to leave—“including many experienced police officers,” according to Camille.

“The ICC can only do a few cases because it has limited resources,” says Alex Whiting, the American magistrate who worked as the Investigators Coordinator and then the Prosecutions Coordinator at the International Criminal Court between 2010 and 2013. Thus, throughout the history of the ICC, the prosecutor has had to choose carefully which cases he or she decides to tackle. For even though the budget of the ICC has involved, it remains largely insufficient.Between 2013 and 2015, the Assembly of States Parties to the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, which votes on the ICC budget, only consented to an increase of 13%. The ICC budget is 130 million euros, even though the court experienced a “doubling of its workload” over these three years, as reported the French Court of Auditors, which conducts audits of public institutions, in a report in 2015. In particular, these additional funds allow for the deployment of more investigators. In 2014, the Office of the Prosecutor had 405 employees, including 63 investigators. In a report shared in late 2014 with the Assembly of State Parties, the Office of the Prosecutor noted that, by comparison, about 840 Dutch police officers participated in the investigation of the disappearance of Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 over the Indian Ocean in 2014.It’s a good reminder of the severe limits in resources for a court that is supposed to monitor impunity in war crimes in the 124 countries that are signatories to the Rome Statute– and whose jurisdiction could extend to the whole world if the UN Security Council asks it to. France, which is the third largest contributor to the ICC budget (after Japan and Germany but ahead of the United Kingdom), is among those countries that adhere to “zero nominal growth of the budget.”

HOW MEDIA CONCERNS SIDELINED

CRIMES OF SEXUAL VIOLENCE

The ICC’s first trial—that of Thomas Lubanga Dyilo, the Congolese military chief—began in January 2009. During a hearing, the Under-Secretary-General of the United Nations, Special Representative for Children and Armed Conflict, Radhikha Coomaraswamy, tried to put the question of sexual violence on the table.

Sexual violence “is part of the use of child soldiers, especially girls,” she said.

Her words were in vain. The charges in the case were calibrated to reflect the limited resources of the Office of the Prosecutor: they focused on the conscription of children under the age of 15 and stopped there.

“There were always difficult choices: Lubanga is a good example,” Moreno-Ocampo said in an email to Zero Impunity. “I had to decide [between] continuing the investigation to prove more charges [against Lubanga] or taking advantage of the opportunity to arrest him and present a case immediately and start the first judicial proceedings.”

In July 2012, Thomas Lubanga Dyilo was sentenced to 14 years in prison. He had never been charged with sexual violence.

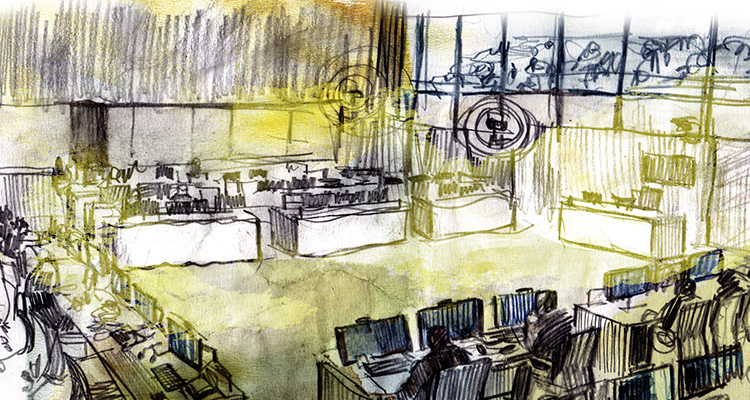

- The courtroom of the International Criminal Court based in The Hague. (© Damien Roudeau – 2017)

The same scenario repeated itself when an investigation was launched in Uganda in July 2004 into massacres committed by the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA), a bloodthirsty, sectarian militia. Of the five arrest warrants issued by the ICC in 2005, only the two targeting the two highest officials—Joseph Kony and Vincent Otti—included charges of rape and sexual slavery. The three other arrest warrants—for Dominic Ongwen, Matthew Lukwiya and Okot Odhiambo—made no mention of these crimes.

“Sexual crimes were so predominant in the whole criminality in the LRA and, ultimately, the charges were not a true reflection of that,” said Richard*, a former ICC employee.

But this case was also shaped by undue urgency.

Moreno-Ocampo put pressure on his teams to follow up as quickly as possible on the arrest warrants, “to show the world that he got results,” according to Richard.

The urgent need of the prosecutor to prove himself seems to have been given priority over convictions for sexual violence. Moreno-Ocampo who, in the past had hosted an Argentinian reality show about justice, “tended to play with the media”, remembered Camille. Moreno-Ocampo took on the role of the first ambassador of the ICC. During his term, he opened the doors of the institution for the filming of four different documentaries.

Yet the image that Moreno-Ocampo presented to the outside world and the press– that of the arch enemy of impunity– stood in contrast with his internal reputation. Especially his reputation as a man who preferred colleagues who “wore skirts,” according to Denis.

When whistleblower Christian Palme went public with his concerns with Moreno-Ocampo’s behavior towards women, it could have tarnished the image that the prosecutor worked so hard to create. The ICC tried to muffle the scandal as soon as it emerged.

“The boss had done

something very bad”

What if the prosecutor had engaged in very serious misconduct that would stain the “high moral character” that his position requires? On March 29, 2005, Christian Palme, Public Information Adviser for the Office of the Prosecutor, found himself wondering just that.

On that day, Palme received an email from a colleague, Yves Sorokobi. Sorokobi seemed embarrassed because “the boss had done something very bad,” as states the transcript of the discussion between the two men, which was included in the complaint filed by Palme against Moreno-Ocampo.

He alleged that Moreno-Ocampo had sexually abused a journalist when he was on a work trip to South Africa in March 2005. On that day, the prosecutor had just finished an interview held in the hotel where he was staying. When the reporter—whose name remains confidential—made to leave, Moreno-Ocampo allegedly took her car keys and led her to his room. There, he forced her to have a sexual relation.

Yves Sorokobi, who is a friend of the journalist, spoke to her on the phone soon after the incident. Sorokobi made a secret recording as she explained, visibly “upset”, what had happened.

Eight months later, on November 30, it was Palme’s turn to make a secret recording as Sorokobi told him about the alleged aggression of the journalist. During the meeting between the two men, Sorokobi played Palme the recording he had made in March of his friend, the journalist.

On October 20, 2006, Palme filed an internal complaint, alleging that Moreno-Ocampo had “committed serious misconduct . . . by committing the crime of rape, or sexual assault, or sexual coercion, or sexual abuse”.

A panel of ICC judges found Palme’s complaint “manifestly unfounded” according to the ruling filed on May 8, 2008 by the International Labour Organization, which Zero Impunity was able to read. On March 16, 2007, Palme was fired for “serious misconduct.” According to the ICC, Palme had formulated false allegations.

However, Palme didn’t give up. Instead, he appealed to the Administrative Tribunal of the International Labor Organisation (ILOAT), which has jurisdiction to settle labor disputes between many international organizations and their employees.

ILOAT ruled in Palme’s favor and condemned the prosecutor’s decision to fire the whistleblower. In its ruling, ILOAT stated that the proof provided by Palme, including the recording that he made of Sorokobi, was “secondary evidence but, depending on the circumstances, it may have been probative in criminal proceedings.”

The ICC was ordered to pay Palme a sum of 240,000 euros in damages.

For the time being, there has been no follow-up on this case within the ICC, nor in South African courts, as the alleged victim did not file a complaint.

“The ILO considered that Mr. Palme’s malicious intent was not proven and ordered compensation,” Moreno-Ocampo said [in an email] to Zero Impunity.

Moreno-Ocampo eventually left the ICC four years later at the end of his term.

Mausoleums versus

raped women

In June 2012, Moreno-Ocampo was replaced by his deputy, the Gambian judge Fatou Bensouda, who had been elected several months prior.

In 2014, she wrote a “Policy paper on sexual and gender-based crimes”: now, there was hope that these crimes would be systematically examined. In 2016, she added new charges of sexual violence in the case against Dominic Ongwen, a Ugandan militia man arrested in January 2015. Unfortunately, these declarations didn’t stop the ICC from falling back into its old habits.

- Gambian magistrate Fatou Bensouda is the ICC prosecutor since 2012. (© Damien Roudeau – 2017)

In September 2016, the court sentenced a Malian jihadist, Ahmad Al-Faqi Al-Mahdi to nine years in prison for the destruction of mausoleums in Timbuktu, Mali. The verdict was handed down quickly—only four years after the events had occurred in 2012. However, the charges didn’t include the role of the accused in running a moral police force that allegedly perpetrated rape and forced marriage. Once more, victims of sexual violence remained the forgotten of a case that would certainly get extensive media coverage. Fatou Bensouda and the Office of the Prosecutor at the ICC didn’t respond to Zero Impunity’s requests for interviews Moreover, in the cases where sexual violence is included in the charges, the justice sometimes leaves behind some of the victims—those from the winning camp.

The blinders

of victor’s justice

Thus, the judges in the Bemba case—started by Luis Moreno-Ocampo—didn’t convict all of the aggressors in that particular conflict. During this highly publicized first for the court—the first conviction over sexual violence—there was complete and total silence about the rapes committed by opposing side— the men led by François Bozizé.

The International Federation for Human Rights, FIDH, did try plead the case of these victims by sending the prosecutor reports documenting the violence committed by Bozizé’s troops. While this violence was not as widespread as the abuse carried out by Bemba’s troops, it was still significant. A report that the NGO sent to the prosecutor in February 2003 states that 30% of known victims of violence in the conflict in Bangui had suffered at the hands of the rebels. In November 2004, Amnesty reported widespread rapes committed by Bozizé’s men in the towns of Kaga-Bandoro, Bossangoa, Sibut and Damara, among others.

“This case gave the impression that things weren’t done all the way”, says Euphrasie Goungaye, the widow of the French-Central African lawyer Nganatouwa Goungaye Wanfiyo who may have given his life to his campaign to bring justice to victims in the conflict. This human rights activist worked for all of the victims to be heard—including those who had suffered at the hands of Bozizé’s men.

“François Bozizé was afraid of being brought before the ICC,” Goungaye says.

Despite both threats and persuasion— including the offer of an important ministerial posting, the lawyer persisted, continuing to compose files on all the victims of violence who the FIDH had reported to the Office of the Prosecutor.

“But [Nganatouwa] didn’t have time to launch a trial”, his widow says bitterly. On the night of December 28, 2008, his car collided with a truck and the lawyer died immediately.

And if François Bozizé had been investigated by the ICC, would he have cooperated and shared incriminating evidence against himself as required by the Rome Statute?

Would the ICC, lacking police, have been able to force him to cooperate? It’s not sure.

On the other hand, Jean-Pierre Bemba was easily arrested in Brussels by Belgian authorities on May 24, 2008 while he was in exile from his home country.

Ange-Félix Patassé, the ousted Central African president who had called on Bemba’s men to help keep a hold on power, found refuge in Togo, a country that is not a signatory of the Rome Statute. No warrant was ever filed for his arrest. He died in April 2011 in Cameroon without ever being punished for the crimes he committed.

The arrest of Jean-Pierre Bemba occurred in the midst of political disgrace for the MLC chief, who had been aiming for the presidency. On October 29, 2006, Bemba lost the second round of presidential elections in the DRC to Joseph Kabila, after violent clashes across the country.

Bemba “was problematic, compromised peace in the country,” according to former ICC employees.

Did the ICC arrest Bemba for political reasons, so as to favor the election of Joseph Kabila? Moreno-Ocampo’s choice to put another Congolese person, prosecutor Jean-Jacques Bandibanga, in charge of the investigation only fed rumors about the political nature of the investigation, which focused solely of Bemba.

- Jean-Pierre Bemba was convicted as a warlord by the ICC, including rape as war crimes and crimes against humanity. (© Damien Roudeau – 2017)

Diplomats at the Court,

an ICC problem

Accusations that the ICC is politicized in its quests for justice are supported by its ongoing relationship with diplomatic circles. After all, the institution includes many former civil servants who once worked in foreign ministries in its ranks.

Since its creation, the Office of the Prosecutor has had a Jurisdiction, Complementarity and Cooperation Department (JCCD).

The JCCD are “the prosecutor’s diplomats,” says Denis*, an ICC employee. The department, a sort of antechamber of the Office of the Prosecutor, was led in its first seven years of existence by two diplomats: between 2003 and 2006, it was led by Silvia Fernandez de Gurmendi, the former Director General for Human Rights in the Argentinian Foreign Ministry, and then, between 2006 and 2010 by Béatrice Le Fraper du Hellen, an French advisor on French foreign relations, who is currently France’s ambassador to Malta. Béatrice Le Fraper du Hellen did not respond to Zero Impunity’s requests for an interview

The blend of diplomacy and judiciary is necessary because “before launching an investigation, there is the process of identifying the political problems that the investigation may pose,” according to Camille.

But, for others, the division between these two roles is too great.

“I thought that [the staff of the JCCD] were supposed to facilitate us but instead it looked like they were deciding things [in terms of investigations,” remembered Richard. “I have always felt that the JCCD at that time was not much in favor of arrests, and it had to do with the peace negotiation that were ongoing at the time.”

However, judge Silvia Fernandez de Gurmendi, current president of the ICC, maintains that “neither JCCD nor any other division or section of the Court could have the function or the power to compromise the judicial work of the Court.”

- In the courtroom of the ICC, lawyers, magistrates and bailiffs come from all continents. (© Damien Roudeau – 2017)

Currently, the Office of the Prosecutor is examining ten “situations”, including one in Colombia, that was launched ten years ago, over crimes committed during the conflict between Colombian authorities and the FARC, including sexual violence. For the time being, however, no investigation has been opened.

“An institution like this, without police, which must rely on the cooperation of States to carry out its arrest warrants is forced to engage with diplomatic resources”, admits a former ICC prosecutor.

Investigations led by the office into post-election violence in Kenya between 2007 and 2008, when more than 900 people were victim to sexual violence, has suffered from this lack of police. Since the investigation was launched in 2009, Uhuru Kenyatta—the main suspect—has become president of Kenya in 2013. Another of the accused, Francis Muthaura, was named head of civil service.

The ICC encountered obstructions erected by the incriminated government. Intimidated witnesses retracted their testimonies. Ultimately, the Office and its judges abandoned the charges against the two accused men.

Diplomatic interference in the cases considered by the ICC extends well beyond the realm of the Jurisdiction, Complementarity and Cooperation Department (JCCD) within the Office of the Prosecutor–indeed, it touches the very makeup of the ICC, for State Parties also place their diplomats amongst the 18 CPI judges. Today, there are five CPI judges who worked in embassies or in their country’s foreign ministries before joining the CPI. This is because it isn’t necessary to have prior experience as a judge to have a seat at the ICC, but simply to “have established competence in relevant areas of international law,”according to the Rome Statute. “All judges at the [International Criminal] Court are jurists that have extensive legal competence and experience in the areas of law that are considered relevant for our work in accordance with its treaty, the Rome Statute,” said Silvia Fernandez de Gurmendi, judge and president of the ICC. Candidates are first nominated to two lists depending on their competencies before being elected to the ICC by the Assembly of States Parties. List A is made up of candidates who have established competence in criminal law and procedure, while serving as a judge, prosecutor, advocate or in other similar capacity, in criminal proceedings. List B, however, is for candidates with “established competence in relevant areas of international law such as international humanitarian law and the law of human rights, and extensive experience in a professional legal capacity which is of relevance to the judicial work of the Court”, according to the Rome Statute. Elections are organised so that there are always at least nine serving judges from List A and at least five from List B.Candidates can also be selected by country representatives at the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA), who are often diplomats. The way that judges are selected at the ICC as well as their individual profiles are both cause for questions. “Personally, I was never approached by the French embassy”, said Claude Jorba, a Frenchman who formerly served on the ICC and whose candidacy was validated by members of the French group at the Permanent Court of Arbitration. “But is this true for all of the judges who were nominated by their countries? Personally, I don’t know.”Moreover, diplomats occupy about half of the seats on the Advisory Committee on Nominations of Judges (ACN), which is supposed to monitor the quality of ICC judicial candidacies.

Decreasing support for the ICC

Suspicions of political instrumentalization with the ICC has undermined its credibility in the eyes of more and more of the 34 African countries who are signatories of the Rome Statute, who feel targeted. Indeed, since its creation, the ICC has only tried Africans. It’ll be difficult for the court to emerge from this situation, because permanent members of the Security Council, China and Russia, are among those who don’t recognize its jurisdiction. Incidentally, these two countries vetoed the UN’s calls to investigate crimes, including rape, committed in Syria.

The contestation of African countries has ended up aiding Omar Al-Bashir, president of Sudan, for whom the court released an arrest warrant in 2009 for crimes including thousands of rapes committed by the Jangawid militias that he led.

Since then, the Sudanese leader has traveled to several different countries on the continent. Each time, he wasn’t arrested. One of the places he visited was South Africa. A year later, the country announced its desire to leave the ICC. Ultimately, the country’s Supreme Court blocked the government’s withdrawal bid.

However, on January 31, 2017, the African Union approved a strategy for collective withdrawal from the Rome Statute. While this decision doesn’t force all members of the AU to withdraw, it does give voice to the opponents of the ICC– of which, there are more and more. Now, Kenya, Burundi and Uganda among others have all lined up behind South Africa in its exasperation with the ICC.

- The International Criminal Court (ICC) is based in The Hague, Netherlands. (© Damien Roudeau – 2017)

In the courtroom of the ICC, on May 16, 2016, Mélanie*, the second victim to testify, appears on the flat screen to describe the ordeal she has been through since being gang-raped. She was infected with AIDs and is often sick. She has had trouble paying for medicine since her father died. A witness to the rape of his daughter, Mélanie’s father’s body was found in a mass grave. Thirteen years after the incident, Mélanie still hasn’t told her children any of this—she doesn’t want to “disturb” them. But in the chill of the courtroom, the victim sighs.

“I feel good, liberated, relieved, because I was able to say what I’ve had to say for years.”

*These names were changed.

«The anonymous, blurry silhouette of “Madame Witness”appears on the flat screen in the courtroom. In a computerized voice, she speaks a few words in Sango, the primary language of the Central African Republic.

Madame Witness isn’t sitting in the courtroom of the International Criminal Court (the ICC) in The Hague, in the Netherlands. She is more than 5,000 kilometers away in Bangui, the capital of the Central African Republic.

“Madame Witness, you are present today thanks to video technology, to speak to us about what you saw as well as your concerns,” says Sylvia Steiner, the Brazilian judge who is presiding over this trial.

Long seconds of silence elapse after each sentence spoken by the witness as her words are translated into French and English, the two working languages of the magistrates, lawyers and bailiffs from five different continents who make up the ICC. Today—May 16, 2016—is a historic day. After 330 days of hearings, a military chief has been convicted of rape as a war crime and a crime against humanity– for the first time in the history of the court.

In this sterilized room, the former Congolese statesman Jean-Pierre Bemba, who stuffed into a dark suit and supervised by two police officers, has lost his splendor.

With a bleak expression, he stares at the screen as the witness testifies—his head sunken into his imposing shoulders. Sometimes, his eyes lift to the sparsely populated rows where a handful of people observe the trial. Mute, he has the resigned expression of someone has already accepted his fate.

Indeed, several months before– on March 21, 2016– Bemba had already been found guilty of two counts of crimes against humanity (murder and rape) and three counts of war crimes (murder, rape, and pillaging) for the crimes committed by the soldiers under his effective authority. The trial today will determine how many years he will be imprisoned for the acts of violence committed by his troops.

Madame Witness is one of 5,229 female victims of violence perpetrated between October 26, 2002 and March 15, 2003 in the Central African Republic by the 1,500 men of the Movement for the Liberation of Congo (MLC), the militia founded by Bemba. A frightening majority of these victims were raped. Today, the judges will hear testimonies from two of these victims, Flavie* and Mélanie*. Both of these women’s lives were deeply, irreparably scarred by the abuse that they endured at the hand’s of Bemba’s men.

These women’s ordeal began when Bemba’s troops came to the aid of Ange-Felix Patassé, the then-president of the Central African Republic (CAR), who was threatened by a coup d’état led by his political rival François Bozizé and his rebels.

Convinced that a majority of Central African civilians had supported Bozizé’s men in their attempt to overthrow Patassé, Bemba and his fellow MLC chiefs instructed their troops to launch a vast punitive operation. At the time, Flavie says she was 15 or 16 years old. The teenager was kidnapped by Bemba’s men, along with her aunt. The two women were taken to a MLC camp.

“When I arrived at their base, one of their chiefs dragged me into an abandoned home […] and raped me,” Flavie recalls. After that, Flavie was imprisoned with other women, some of whom were as young as 13, and forced to move along with the troops. She was raped every day. Eventually, Bemba’s men retreated back to the DRC, bringing Flavie with them. There, she found out she was pregnant and was forced to live with one of her rapists. Her first child died early, but Flavie soon gave birth to a second.

After four years, Flavie and her daughter managed to flee the DRC. They made their way back to the CAR to reunite with Flavie’s family, who had given their daughter up for dead. Flavie’s aunt—who had also been kidnapped and raped by Bemba’s men—had also made it back alive. However, return to normal life was impossible for these women.

Flavie’s aunt, who had contracted HIV, was unable to access treatment and soon died. Bemba’s men had taken everything from Flavie’s family and they were now living in extreme poverty. Flavie couldn’t return to school. Stigmatized by her neighbors, Flavie decided to leave her hometown and move to Bangui, the capital.

Flavie did eventually get married. However, today, she is a widow, left alone to support her four children as her in-laws rejected her when they found out about her rape. Flavie has no income and is suicidal. She and her children now live with an aunt. Flavie’s oldest daughter doesn’t know she was born of rape.

“The ICC’s ruling won’t change my living situation,” she says. “But someone must pay for the violence that was perpetrated.”

Justice was served for Flavie, Mélanie and the other victims of the brutal campaign led by Bemba’s men in the Central African Republic. However, they are the only ones to achieve this minor success. All of the other victims of sexual violence who have sought justice through the ICC haven’t had that chance.

It took 14 years for the court to sentence a high-ranking official for sexual violence, even though sexual violence is considered a crime under the Statute of Rome, the founding text of the ICC.

However, since the ICC was created in 2002, the court has only accepted to examine about a third of cases involving sexual violence. Moreover, out of the only three cases including charges of sexual violence tried by the court, two ended with acquittals—a surprising record considering that all of the situations subject to ICC investigations have been the site of mass sexual violence. Even in the DRC– a country that is notorious for widespread instances of rape–the court has not achieved even a single conviction. This failure results from a combination of lack of funds and the misguided methods of the ICC.

Investigations: undue haste

and frequent setbacks

The ICC Prosecutor is at the very heart of the system that launches investigations, determines investigation strategies and identifies suspects. When Luis Moreno-Ocampo became the very first person nominated to this post in 2003—shortly after the creation of the court– he was tasked with identifying goals for his team.

However, when he took office in 2004, the ICC was still taking shape. Just about everything still needed to be done, including recruitment of personnel, organization and the creation of different services. This made for laborious beginnings for the Office of the Prosecutor.

Investigators had to start at zero. In the first few months, there were only two investigators covering the entire Democratic Republic of Congo. Working conditions were difficult—they didn’t have an office or a car and they weren’t provided with housing. Security in the country remained uncertain. However, after the first wave of recruitments, the ICC investigators working on the DRC increased: by 2005, there were 12 of them. However, amongst their number, there were few police officers.

That was how Moreno-Ocampo wanted it. The exuberant Argentinian prosecutor saw himself as the herald of a new age of international criminal justice.

“Think out of the box!” he would exclaim to his skeptical team.

“This kind of declaration drove many of the legal experts crazy!” recounted Sacha*, another employee of the court.

Moreno-Ocampo was against the idea of recruiting police officers in his teams and preferred former NGO employees, who he thought to be more familiar with the geopolitical context of the countries that they would be working on.

“We have experienced that in many cases the national police investigators in countries had developed contacts and obtained sources within the militias under investigation,” Moreno-Ocampo stated in an email exchange with Zero Impunity. “Investigators with a different [non-police] background developed sources within the victims’ communities. We just used different approaches.”

For some people who worked within the Office of the Prosecutor, Moreno-Ocampo’s reluctance to employ police officers as investigators was linked to his own personal story and that of his country.

Moreno-Ocampo participated in the trial of the former military junta in his native Argentina in the 1980s. That investigation taught Moreno-Ocampo to work with NGOs instead of the police, many of whom had closely collaborated with the former regime.

While “brilliant,” the young ICC recruits who had formerly worked with NGOs “didn’t know how to collect proof, carry out rigorous interrogations or manage sources,” said Denis*, an ICC employee who knew the prosecutor and who agreed to speak with Zero Impunity. This lack of experience was enough to slow down investigations that were already progressing with great difficulty.

However, the impulsive Argentinian was determined to prove to the world that the court had power and drive. No matter the lack of funds, it was important to rapidly bring cases in front of the judges, who were becoming impatient.

The prosecutor decided to focus his team’s efforts on isolated massacres and targeted incidents. It was a method that, for some, was much too narrow.

“The likelihood of stumbling upon an incident that we could trace back to a high official were slim,” Denis said.

The prosecutor made “abrupt changes” to the focuses of the investigations that were being led by his teams, according to Camille*, a former court employee. Investigators were exploring leads on several massacres where rapes were committed—which could have been traced back to the orders of high-ranking officials– but were forced to suddenly abandoned their research because of time pressures.

Investigators were exploring leads on several massacres where rapes were committed but were forced to suddenly abandoned their research because of time pressures.

Moreno-Ocampo wanted to strike quickly and powerfully, especially when, in 2006, the court caught its first big fish, Thomas Lubanga Dyilo, a Congolese war chief, who was handed over to the ICC by authorities in Kinshasa. Moreno-Ocampo made a strategic choice to focus on what happened to child soldiers conscripted in Lubanga’s militia. Because of this narrow focus on child soldiers, all of the sexual violence committed by the militia would be set aside.

According to former ICC employee Camille, certain NGOs that had an “in” at the ICC had suggested the theme of this investigation. The West was rightly horrified by the conscription of child soldiers. However, for the Congolese, “the infractions that caused the most suffering for the population were the raping and pillaging,” Camille said.

Perhaps the prosecutor thought he had stumbled on a case that would be easy to carry out, as well as being symbolic. However, the teams working for the Office of the Prosecutor started asking an important question: “How do you prove the age of children in a country where birth records aren’t reliable?” asked Camille. These were questions that Moreno-Ocampo disregarded when he threw himself into this crusade. He said criticisms and differences of opinion were to be expected.

“We were a global start up working for a global audience with different opinions,” Moreno-Ocampo said in an email to Zero Impunity. “At the beginning, it was very difficult to harmonize the practices, creating disagreements.”

However, tensions continued to grow within the Office of the Prosecutor and Moreno-Ocampo’s heavy-handedness didn’t help matters.

Between 2005 and 2007, frustration, inability to understand the strategies used in investigations and erratic changes to objectives pushed a part of the Office’s workforce to leave—“including many experienced police officers,” according to Camille.

“The ICC can only do a few cases because it has limited resources,” says Alex Whiting, the American magistrate who worked as the Investigators Coordinator and then the Prosecutions Coordinator at the International Criminal Court between 2010 and 2013. Thus, throughout the history of the ICC, the prosecutor has had to choose carefully which cases he or she decides to tackle. For even though the budget of the ICC has involved, it remains largely insufficient.Between 2013 and 2015, the Assembly of States Parties to the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, which votes on the ICC budget, only consented to an increase of 13%. The ICC budget is 130 million euros, even though the court experienced a “doubling of its workload” over these three years, as reported the French Court of Auditors, which conducts audits of public institutions, in a report in 2015. In particular, these additional funds allow for the deployment of more investigators. In 2014, the Office of the Prosecutor had 405 employees, including 63 investigators. In a report shared in late 2014 with the Assembly of State Parties, the Office of the Prosecutor noted that, by comparison, about 840 Dutch police officers participated in the investigation of the disappearance of Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 over the Indian Ocean in 2014.It’s a good reminder of the severe limits in resources for a court that is supposed to monitor impunity in war crimes in the 124 countries that are signatories to the Rome Statute– and whose jurisdiction could extend to the whole world if the UN Security Council asks it to. France, which is the third largest contributor to the ICC budget (after Japan and Germany but ahead of the United Kingdom), is among those countries that adhere to “zero nominal growth of the budget.”

How media concerns

sidelined crimes of sexual violence

The ICC’s first trial—that of Thomas Lubanga Dyilo, the Congolese military chief—began in January 2009. During a hearing, the Under-Secretary-General of the United Nations, Special Representative for Children and Armed Conflict, Radhikha Coomaraswamy, tried to put the question of sexual violence on the table.

Sexual violence “is part of the use of child soldiers, especially girls,” she said.

Her words were in vain. The charges in the case were calibrated to reflect the limited resources of the Office of the Prosecutor: they focused on the conscription of children under the age of 15 and stopped there.

“There were always difficult choices: Lubanga is a good example,” Moreno-Ocampo said in an email to Zero Impunity. “I had to decide [between] continuing the investigation to prove more charges [against Lubanga] or taking advantage of the opportunity to arrest him and present a case immediately and start the first judicial proceedings.”

In July 2012, Thomas Lubanga Dyilo was sentenced to 14 years in prison. He had never been charged with sexual violence.

The same scenario repeated itself when an investigation was launched in Uganda in July 2004 into massacres committed by the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA), a bloodthirsty, sectarian militia. Of the five arrest warrants issued by the ICC in 2005, only the two targeting the two highest officials—Joseph Kony and Vincent Otti—included charges of rape and sexual slavery. The three other arrest warrants—for Dominic Ongwen, Matthew Lukwiya and Okot Odhiambo—made no mention of these crimes.

“Sexual crimes were so predominant in the whole criminality in the LRA and, ultimately, the charges were not a true reflection of that,” said Richard*, a former ICC employee.

But this case was also shaped by undue urgency.

Moreno-Ocampo put pressure on his teams to follow up as quickly as possible on the arrest warrants, “to show the world that he got results,” according to Richard.

The urgent need of the prosecutor to prove himself seems to have been given priority over convictions for sexual violence. Moreno-Ocampo who, in the past had hosted an Argentinian reality show about justice, “tended to play with the media”, remembered Camille. Moreno-Ocampo took on the role of the first ambassador of the ICC. During his term, he opened the doors of the institution for the filming of four different documentaries.

Yet the image that Moreno-Ocampo presented to the outside world and the press– that of the arch enemy of impunity– stood in contrast with his internal reputation. Especially his reputation as a man who preferred colleagues who “wore skirts,” according to Denis.

When whistleblower Christian Palme went public with his concerns with Moreno-Ocampo’s behavior towards women, it could have tarnished the image that the prosecutor worked so hard to create. The ICC tried to muffle the scandal as soon as it emerged.

“The boss had done

something very bad”

What if the prosecutor had engaged in very serious misconduct that would stain the “high moral character” that his position requires? On March 29, 2005, Christian Palme, Public Information Adviser for the Office of the Prosecutor, found himself wondering just that.

On that day, Palme received an email from a colleague, Yves Sorokobi. Sorokobi seemed embarrassed because “the boss had done something very bad,” as states the transcript of the discussion between the two men, which was included in the complaint filed by Palme against Moreno-Ocampo.

He alleged that Moreno-Ocampo had sexually abused a journalist when he was on a work trip to South Africa in March 2005. On that day, the prosecutor had just finished an interview held in the hotel where he was staying. When the reporter—whose name remains confidential—made to leave, Moreno-Ocampo allegedly took her car keys and led her to his room. There, he forced her to have a sexual relation.

Yves Sorokobi, who is a friend of the journalist, spoke to her on the phone soon after the incident. Sorokobi made a secret recording as she explained, visibly “upset”, what had happened.

Eight months later, on November 30, it was Palme’s turn to make a secret recording as Sorokobi told him about the alleged aggression of the journalist. During the meeting between the two men, Sorokobi played Palme the recording he had made in March of his friend, the journalist.

On October 20, 2006, Palme filed an internal complaint, alleging that Moreno-Ocampo had “committed serious misconduct . . . by committing the crime of rape, or sexual assault, or sexual coercion, or sexual abuse”.

A panel of ICC judges found Palme’s complaint “manifestly unfounded” according to the ruling filed on May 8, 2008 by the International Labour Organization, which Zero Impunity was able to read. On March 16, 2007, Palme was fired for “serious misconduct.” According to the ICC, Palme had formulated false allegations.

On March 16, 2007, Palme was fired for “serious misconduct.” According to the ICC, Palme had formulated false allegations.

However, Palme didn’t give up. Instead, he appealed to the Administrative Tribunal of the International Labor Organisation (ILOAT), which has jurisdiction to settle labor disputes between many international organizations and their employees.

ILOAT ruled in Palme’s favor and condemned the prosecutor’s decision to fire the whistleblower. In its ruling, ILOAT stated that the proof provided by Palme, including the recording that he made of Sorokobi, was “secondary evidence but, depending on the circumstances, it may have been probative in criminal proceedings.”

The ICC was ordered to pay Palme a sum of 240,000 euros in damages.

For the time being, there has been no follow-up on this case within the ICC, nor in South African courts, as the alleged victim did not file a complaint.

“The ILO considered that Mr. Palme’s malicious intent was not proven and ordered compensation,” Moreno-Ocampo said [in an email] to Zero Impunity.

Moreno-Ocampo eventually left the ICC four years later at the end of his term.

Mausoleums versus

raped women

In June 2012, Moreno-Ocampo was replaced by his deputy, the Gambian judge Fatou Bensouda, who had been elected several months prior.

In 2014, she wrote a “Policy paper on sexual and gender-based crimes”: now, there was hope that these crimes would be systematically examined. In 2016, she added new charges of sexual violence in the case against Dominic Ongwen, a Ugandan militia man arrested in January 2015. Unfortunately, these declarations didn’t stop the ICC from falling back into its old habits.

In September 2016, the court sentenced a Malian jihadist, Ahmad Al-Faqi Al-Mahdi to nine years in prison for the destruction of mausoleums in Timbuktu, Mali. The verdict was handed down quickly—only four years after the events had occurred in 2012. However, the charges didn’t include the role of the accused in running a moral police force that allegedly perpetrated rape and forced marriage. Once more, victims of sexual violence remained the forgotten of a case that would certainly get extensive media coverage. Fatou Bensouda and the Office of the Prosecutor at the ICC didn’t respond to Zero Impunity’s requests for interviews Moreover, in the cases where sexual violence is included in the charges, the justice sometimes leaves behind some of the victims—those from the winning camp.

The blinders

of victor’s justice

Thus, the judges in the Bemba case—started by Luis Moreno-Ocampo—didn’t convict all of the aggressors in that particular conflict. During this highly publicized first for the court—the first conviction over sexual violence—there was complete and total silence about the rapes committed by opposing side— the men led by François Bozizé.

The International Federation for Human Rights, FIDH, did try plead the case of these victims by sending the prosecutor reports documenting the violence committed by Bozizé’s troops. While this violence was not as widespread as the abuse carried out by Bemba’s troops, it was still significant. A report that the NGO sent to the prosecutor in February 2003 states that 30% of known victims of violence in the conflict in Bangui had suffered at the hands of the rebels. In November 2004, Amnesty reported widespread rapes committed by Bozizé’s men in the towns of Kaga-Bandoro, Bossangoa, Sibut and Damara, among others.

“This case gave the impression that things weren’t done all the way”, says Euphrasie Goungaye, the widow of the French-Central African lawyer Nganatouwa Goungaye Wanfiyo who may have given his life to his campaign to bring justice to victims in the conflict. This human rights activist worked for all of the victims to be heard—including those who had suffered at the hands of Bozizé’s men

“François Bozizé was afraid of being brought before the ICC,” Goungaye says.

Despite both threats and persuasion— including the offer of an important ministerial posting, the lawyer persisted, continuing to compose files on all the victims of violence who the FIDH had reported to the Office of the Prosecutor.

“But [Nganatouwa] didn’t have time to launch a trial”, his widow says bitterly. On the night of December 28, 2008, his car collided with a truck and the lawyer died immediately.

And if François Bozizé had been investigated by the ICC, would he have cooperated and shared incriminating evidence against himself as required by the Rome Statute?

Would the ICC, lacking police, have been able to force him to cooperate? It’s not sure. On the other hand, Jean-Pierre Bemba was easily arrested in Brussels by Belgian authorities on May 24, 2008 while he was in exile from his home country.

Ange-Félix Patassé, the ousted Central African president who had called on Bemba’s men to help keep a hold on power, found refuge in Togo, a country that is not a signatory of the Rome Statute. No warrant was ever filed for his arrest. He died in April 2011 in Cameroon without ever being punished for the crimes he committed.

The arrest of Jean-Pierre Bemba occurred in the midst of political disgrace for the MLC chief, who had been aiming for the presidency. On October 29, 2006, Bemba lost the second round of presidential elections in the DRC to Joseph Kabila, after violent clashes across the country.

Bemba “was problematic, compromised peace in the country,” according to former ICC employees.

Did the ICC arrest Bemba for political reasons, so as to favor the election of Joseph Kabila? Moreno-Ocampo’s choice to put another Congolese person, prosecutor Jean-Jacques Bandibanga, in charge of the investigation only fed rumors about the political nature of the investigation, which focused solely of Bemba.

Diplomats at the Court,

an ICC problem

Accusations that the ICC is politicized in its quests for justice are supported by its ongoing relationship with diplomatic circles. After all, the institution includes many former civil servants who once worked in foreign ministries in its ranks.

Since its creation, the Office of the Prosecutor has had a Jurisdiction, Complementarity and Cooperation Department (JCCD).

The JCCD are “the prosecutor’s diplomats,” says Denis*, an ICC employee. The department, a sort of antechamber of the Office of the Prosecutor, was led in its first seven years of existence by two diplomats: between 2003 and 2006, it was led by Silvia Fernandez de Gurmendi, the former Director General for Human Rights in the Argentinian Foreign Ministry, and then, between 2006 and 2010 by Béatrice Le Fraper du Hellen, an French advisor on French foreign relations, who is currently France’s ambassador to Malta. Béatrice Le Fraper du Hellen did not respond to Zero Impunity’s requests for an interview

The blend of diplomacy and judiciary is necessary because “before launching an investigation, there is the process of identifying the political problems that the investigation may pose,” according to Camille.

But, for others, the division between these two roles is too great.

“I thought that [the staff of the JCCD] were supposed to facilitate us but instead it looked like they were deciding things [in terms of investigations,” remembered Richard. “I have always felt that the JCCD at that time was not much in favor of arrests, and it had to do with the peace negotiation that were ongoing at the time.”

However, judge Silvia Fernandez de Gurmendi, current president of the ICC, maintains that “neither JCCD nor any other division or section of the Court could have the function or the power to compromise the judicial work of the Court.”

Currently, the Office of the Prosecutor is examining ten “situations”, including one in Colombia, that was launched ten years ago, over crimes committed during the conflict between Colombian authorities and the FARC, including sexual violence. For the time being, however, no investigation has been opened.

“An institution like this, without police, which must rely on the cooperation of States to carry out its arrest warrants is forced to engage with diplomatic resources”, admits a former ICC prosecutor.

Investigations led by the office into post-election violence in Kenya between 2007 and 2008, when more than 900 people were victim to sexual violence, has suffered from this lack of police. Since the investigation was launched in 2009, Uhuru Kenyatta—the main suspect—has become president of Kenya in 2013. Another of the accused, Francis Muthaura, was named head of civil service.

The ICC encountered obstructions erected by the incriminated government. Intimidated witnesses retracted their testimonies. Ultimately, the Office and its judges abandoned the charges against the two accused men.

Diplomatic interference in the cases considered by the ICC extends well beyond the realm of the Jurisdiction, Complementarity and Cooperation Department (JCCD) within the Office of the Prosecutor–indeed, it touches the very makeup of the ICC, for State Parties also place their diplomats amongst the 18 CPI judges. Today, there are five CPI judges who worked in embassies or in their country’s foreign ministries before joining the CPI. This is because it isn’t necessary to have prior experience as a judge to have a seat at the ICC, but simply to “have established competence in relevant areas of international law,”according to the Rome Statute. “All judges at the [International Criminal] Court are jurists that have extensive legal competence and experience in the areas of law that are considered relevant for our work in accordance with its treaty, the Rome Statute,” said Silvia Fernandez de Gurmendi, judge and president of the ICC. Candidates are first nominated to two lists depending on their competencies before being elected to the ICC by the Assembly of States Parties. List A is made up of candidates who have established competence in criminal law and procedure, while serving as a judge, prosecutor, advocate or in other similar capacity, in criminal proceedings. List B, however, is for candidates with “established competence in relevant areas of international law such as international humanitarian law and the law of human rights, and extensive experience in a professional legal capacity which is of relevance to the judicial work of the Court”, according to the Rome Statute. Elections are organised so that there are always at least nine serving judges from List A and at least five from List B.Candidates can also be selected by country representatives at the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA), who are often diplomats. The way that judges are selected at the ICC as well as their individual profiles are both cause for questions. “Personally, I was never approached by the French embassy”, said Claude Jorba, a Frenchman who formerly served on the ICC and whose candidacy was validated by members of the French group at the Permanent Court of Arbitration. “But is this true for all of the judges who were nominated by their countries? Personally, I don’t know.”Moreover, diplomats occupy about half of the seats on the Advisory Committee on Nominations of Judges (ACN), which is supposed to monitor the quality of ICC judicial candidacies.

Decreasing support for the ICC

Suspicions of political instrumentalization with the ICC has undermined its credibility in the eyes of more and more of the 34 African countries who are signatories of the Rome Statute, who feel targeted. Indeed, since its creation, the ICC has only tried Africans. It’ll be difficult for the court to emerge from this situation, because permanent members of the Security Council, China and Russia, are among those who don’t recognize its jurisdiction. Incidentally, these two countries vetoed the UN’s calls to investigate crimes, including rape, committed in Syria.

The contestation of African countries has ended up aiding Omar Al-Bashir, president of Sudan, for whom the court released an arrest warrant in 2009 for crimes including thousands of rapes committed by the Jangawid militias that he led.

Since then, the Sudanese leader has traveled to several different countries on the continent. Each time, he wasn’t arrested. One of the places he visited was South Africa. A year later, the country announced its desire to leave the ICC. Ultimately, the country’s Supreme Court blocked the government’s withdrawal bid.

However, on January 31, 2017, the African Union approved a strategy for collective withdrawal from the Rome Statute. While this decision doesn’t force all members of the AU to withdraw, it does give voice to the opponents of the ICC– of which, there are more and more. Now, Kenya, Burundi and Uganda among others have all lined up behind South Africa in its exasperation with the ICC.

In the courtroom of the ICC, on May 16, 2016, Mélanie*, the second victim to testify, appears on the flat screen to describe the ordeal she has been through since being gang-raped. She was infected with AIDs and is often sick. She has had trouble paying for medicine since her father died. A witness to the rape of his daughter, Mélanie’s father’s body was found in a mass grave. Thirteen years after the incident, Mélanie still hasn’t told her children any of this—she doesn’t want to “disturb” them. But in the chill of the courtroom, the victim sighs.

“I feel good, liberated, relieved, because I was able to say what I’ve had to say for years.”

*These names were changed.

SHARE

SHARE

ARIANE PUCCINI

Ariane Puccini is co-founder and member of the Youpress collective. For the past 10 years, she has been reporting in France and abroad for the French, francophone and foreign press.

CAMILLE JOURDAN

Holder of a master’s degree in French-English journalism at the Sorbonne Nouvelle, Camille Jourdan is an independent journalist for web and print media. She deals mainly with social topics, from education to the world of work, through the collaborative economy.

WOULD LIKE TO ACT FOLLOWING THIS INVESTIGATION?

WOULD LIKE TO ACT

FOLLOWING THIS INVESTIGATION?

JOIN THE MOVEMENT

#ZEROIMPUNITY

MARCH TO SHOW SUPPORT TO VICTIMS OF SEXUAL VIOLENCE IN THE CURRENT ARMED CONFLICTS.

JOIN THE MOVEMENT

#ZEROIMPUNITY

Do not allow impunity to persist. Sign our petitions.

MARCH TO SHOW SUPPORT TO VICTIMS OF SEXUAL VIOLENCE IN THE CURRENT ARMED CONFLICTS.

Stay Tuned

Follow us

Stay Tuned

Follow us

With the participation of

With the support of